To the past, or the time that manifests itself

Jiro Iio (Editor, speelplaats co., ltd)

The encounter between the graphic designer Yoshihisa Tanaka and the architect Fuminori Nousaku was made possible by several, overlapping fields of senses.

One example was the field of collaboration between the graphic design and the spatial installation for “Cosmo-Eggs|宇宙の卵,” presented at the Japan Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition in 2018. At the pavilion, part of an international exhibition showcasing the works of contemporary artists, a group consisting of an artist, a composer, an anthropologist and an architect collaborated on the installation, combining their films, sounds, texts and spaces. The installation allowed visitors to experience the presence of Tsunami-ishi. Researched and filmed by the artist Motoyuki Shitamichi, the enormous and seemingly immovable rock was carried ashore in the Yaeyama Islands, Okinawa, by the tremendous energy of a tsunami. The rock remembers an immense, instantaneous force that occurred hundreds, perhaps thousands of years ago. It becomes an agent (causing a chain of actions) that stimulates our senses by accumulating a powerful index (mark of nature), something that emits a wholeness that remains uncategorised in its timeliness, eternity and significance. The contemporary art market may be a variation of a macro-economy. The market is not something that can suppress art; it is a complex movement of index-agent and a method of abduction (hypothetical reasoning), which transcends the law that makes a community a community. On the contrary, it is a conjugate made visible by the intent to re-construct art anthropologically, separate from the market. ★1

The time of graphic and the time of architecture. The second overlapping field is their interest in the time that agents carry as characteristics.

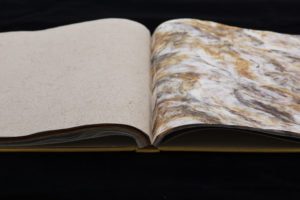

As an expression of graphic design, Tanaka has been making paper. Rather than making digital media, which can be consumed in an instant, or paper media, which can be mass-produced and mass-consumed, he makes a wide variety of Japanese papers that can be produced in small quantities. As a recording media, it has unprecedented accuracy. Numerous stories recorded on Japanese paper during the Heian era can still be recited today, highlighting the notable archival quality of the material. Papers made with materials of high purity, such as kozo pulp, were used as offerings to the nobles, while on the other hand, everyday papers mixed with old, unusable cloths or fishing nets functioned as objects that made visible the network of discarded and scrapped materials. The accumulation of this index in Japanese paper provided stimulation for Tanaka, inspiring him to make works by mixing materials used for Japanese paper with pulverised coal, which is found in soil throughout the country as a result of life during the Jomon and Yayoi eras, more than 10,000 years ago, when people would burn off grasses. His actions inform us of the risks associated with the economy’s exchange market, which is built on a cycle in which 70% of paper products are discarded as trash.

As an architect, Fuminori Nousaku seems to pave the way to a new kind of abduction that verifies unfinished architecture. Based on new observations and assumptions that surpass the modern principles of architectural design and its production, this idea is evident in works such as “Guest House in Takaoka (2016),” for which he demolished, mended and rebuilt a 40-year-old tiled roof house in a different location; and “Hole of Nishi-Ōi,” the home-cum-office where he practices daily cycles of design, construction and life. As an industry, architecture resembles cooking on a large scale with mass-produced and mass-consumed building ingredients, reaching the apex of its production and value upon completion, but prior to consumption. However, is it possible to determine the most valuable point in time when the index-agent continues to construct and renew its abductive nexus (chain)? “Hole of Nishi-Ōi,” a four-storey secondhand residential building built during the bubble era, has been assigned the subtitle of “Wild ecology of the city.” The architect continues to make various holes in the urban residential house, which is an expensive product of a period of economic growth, in order to match his lifecycle and the interior layout. Wild is a word that represents a strong will to move away from a suspended state of nexus.

We can no longer be wild because our living spheres have now been completely marketised. Not only that, but the global environment we live in has become a manmade environment that has driven nature away. This world is known as the Anthropocene. It is an imaginary geologic timescale proposed by the Nobel Prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul Jozef Crutzen in 2000. The explosive increase in population from the mid-twentieth century, the global-scale emission of plutonium isotopes by nuclear tests, and the drastic global urbanisation that has covered the earth with a new concrete skin… these events resulted in the earth’s hidden regions to be swallowed up as the background for the global megalopolis and industry, turning the earth into a single planet-city. Viewed from the perspective of the Earth itself, the Anthropocene would be seen as the result of Anthropocentrism, triggered by the development of agriculture and settlements, domestication of animals, governing and alteration of environments and deprivation of nature, which commenced 10,000 years ago.

— At a time when all of the arts have been commercialised, the process of disassembling the arts into non-arts may in fact paradoxically contribute to leaving the aesthetic space open until “something good appears.” ★2

The contemporary state of the Anthropocene. It is now a story of the past, a time when Anthropocentrism functioned as the incubator of creation, enabling the social system to stratify and stabilise the values of art and architecture.

★1 ── Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory, Oxford University Press, 1998. Akinori Kubo “Reading Alfred Gell’s Art and Agency” (https://kuboakinori.hatenadiary.org/entry/20070623/1182586897, 2007)

★2 ── Timothy Morton “Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics,” Harvard University Press, 2009